|

|

|

|

Lesson 2 |

Hellenistic-Roman Medicine. Arab Medicine. Medieval Times |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alexander the Great conquered all of the Mediterranean but, as often happens, such great expansion ultimately brought about the collapse of Alexander's empire. He left power in the hands of various generals, and so his Empire was divided into numerous kingdoms. Among the most important kingdoms was that of Pergamo and, above all, that of the Ptolemies in Egypt. Here the Greek culture fused with the Egyptian. During the Ptolemies' empire, a cultural movement of vast proportions developed at Alexandria in Egypt. The largest and most famous library in ancient times was built, which contained the sum of the epoch's knowledge, and which, unfortunately, suffered several misfortunes in the following centuries. It was set on fire by Caesar and by other Roman emperors, and was definitively destroyed around 640 by an Arab Caliph. This library was a true and real university in which scientists trained in the Aristotlean school. However, they dissected not only animals, but also humans. Egypt was a land which, for millennia, had practised funerary, so dissection had been performed as a preparation for mummification. Therefore, the technique of postmortem examination acquired importance, not only in terms of dissection, but as also occurred in the Renaissance, as a fundamental part of a doctor's professional activities. Very important was the empirical school, widespread in Alexandria, according to which a doctor's work consisted of three fundamental activities: anamnesis (case history), autopsy (visiting the ill, in the sense of inspecting the patient), and diagnosis. Thus, the school had very interesting principles which bring to mind those of today, but all the same it failed because there was no concrete possibility of either making an accurate diagnosis or consequently, due to their lack of knowledge, providing an ad hoc therapy for the illness. At the same time as the empirical school trained doctors, the dogmatic school which was a continuation of the Hippocratic school and the methodical school, which had a great success, were flourishing in Alexandria. Two outstanding scientists working outside the above-mentioned schools also lived in Alexandria, namely Herophilus (330 B.C.) (1) and Erasistratus (304 B.C.-250 B.C.) . The latter was a great scientist, above all because he was the first to recognise that the arteries are also vessels, opposing Aristotle's belief that arteries did not transport blood but pneuma (2). Moreover, he placed great emphasis on the study of the pulse, on the concept of body temperature etc., contributions which were lost in the course of the following centuries (3).

In Ancient Greek and then, in Roman times, there were great developments in hygiene. The body's physiological needs were no longer carried out in the external environment or in communal open places (streets, clearings...) but in appropriate buildings, public lavatories equipped with a water supply and a sewage system. Rome had an efficient sewage system in addition to an extremely functional water supply system. This was not only for the rich, but included everyone; in the insulae (tenanted houses in ancient Rome), there was a fountain, with running water brought to every house by aqueducts. These aqueducts were constructed using lead pipes, a very malleable material, and were blamed for the fall of the Roman Empire because of the disease caused by lead compounds in the water resulting in lead poisoning, also known as saturnism. In fact, it seems that it was not so much polluted water that caused this illness, but wine. Indeed, water came from mountainous areas and was rich in calcium compounds which were deposited with the passage of time on the inside of the lead pipes and so formed a protective layer keeping the water from the lead which thus could no longer enter into the running water. On the other hand, wine was rich in soluble lead compounds because these were used to control the wine's fermentation in the same way as disulphide is today. Medicine was practiced in a family environment in Rome (the family doctor was the pater familias who had absolute power over the family) and although medicine was not based on any true real theory, it was, however, a rationalised empirical science. The herbalist was very important even if, he too, worked in an empirical manner. Medicine arrived in Rome with the conquest of Greece. To be a doctor in Rome was considered disdainful, something that only a foreigner would do. Since, after its conquest by the Romans, Greece was poverty-stricken after numerous wars had wasted it, there were a great many medics who sold themselves as slaves so as to be able to go to Rome and exercise their profession. Many of these became famous and bought their freedom, becoming freedmen. The sect that enjoyed the best fortune was the Metodic (4), with Asclepėades and his student Temison influencing the Roman medical culture very strongly. Furthermore, there were very important writers of treatises in Rome, among whom was the founder of herbal medicine, Dioscorides Pedanius (First Century A.D.) who published a book entititled De materia medica, which remained the basis of pharmacology until the early 1800s. Soranus of Ephesus (I/II century) , a Greek doctor, published a gynaecological treatise, and above all Aulus Cornelius Celsus (14 B.C.-37 A.D.) with his treatise De Medicina, also were important. The latter textbook was a kind of medical encyclopaedia that discussed arguments of surgery and of medicine from a scholarly point of view rather than that of an expert in the subject, simply compiling a great list of common practices in Rome. This enables us to gain an idea of the development of surgery at that time, above all in particular fields such as dentistry (5).

Furthermore, Galen emphasised other therapeutic methods, such as blood-letting. He also introduced the methodist concept of the pores, but this was distorted into an invitation not to wash oneself because water could obstruct the pores. Galen elaborated a philosophical theory in order to understand how our body functioned and how blood circulated. On the basis of many of Aristotle's assertions (he was the first to consider digestion as a method of processing ingested food in the stomach), Galen maintained that the nutritious substances were then brought to the liver (the principal organ for blood distribution) via the mesenteric veins (the chyliferous vessels had not been discovered at that time). This material became blood in the liver and was enriched in spiritus naturalis (natural spirit). Most of this blood went from the liver, through the veins, to all parts of the body where it was consumed as a nutriment. On the other hand, some blood went through the vena cava to the heart in which burnt the living spiritus vitalis (vital spirit), which in turn enriched the blood. In particular, the blood reached the heart on its right-hand side and from here reached the left-hand side of the heart through the pores of the septum. From here through the arteries, as they were considered to be vessels, the blood above all reached the brain. However, before reaching the brain the blood passed through a special vascular network (the rete mirabile) situated in the neck (9). The blood reaching the encephalon, was enriched by another spirit, the spiritus animalis (animal spirit), and through the nerves, which were considered to be the third system of vessels, it reached the body's organs where it gave life. This theory did not hypothesize that blood circulates, only that it moves: in Galeno's opinion it moved according to the sea's tides. Naturally, this theory could be easily refuted. In reality, if this concepts were true, there would have to be an enormous quantity of blood. If the blood consumed itself as it reached the body's parts, it is logical that the body would continuously consume a notable quantity of it. Slitting the throat of an animal would be enough to demolish this theory, as Harvey did 1500 years later. Furthermore, according to Galen's theory the blood was filtered in the brain, so that its impurities could be discharged through the cribriform plate (a lamina of the ethmoidal bone so-called because it is akin to a sieve - cribrum in Latin) giving rise to tears, saliva, mucus and sweat. Although was a fascinating theory, it had no experimental basis, but, because it fitted well with Christian doctrine, it then became almost a dogma and was still considered to be valid in the 16th century at the times of the great Vesal. In addition to that of the blood, among the Galenic conceits thus rendered untouchable was its anatomy mainly founded on animal studies. As evidence of Galen's unassailable position is the fact that, notwithstanding all the evidence presented by any skeleton seen by any physician, for more than a millennium anatomists went on to assert that the humerus is curved and that any straight ones were nothing else than tricks played by nature. After Galen there was a multitude of medics who worked in the Western empire, but also in the Eastern empire with a consequent diffusion of knowledge from the West to the East. In the wake of the great importance placed on hygiene the first true and real hospitals were built in Roman times. As reported by Vitruvius, they had facilities such as waste disposal, a water supply system, sewerage, and free circulation of air as evidenced by the numerous windows with which these hospitals were provided. In parallel with the transfer of power to Byzantium, there was a transfer of the medical culture and hygiene too. Baths and hospitals were numerous, and social medicine made its appearance. There were famous doctors such as Paul of Egina in the city of Byzantium, but these did nothing else but repeat what Galen had said. In Byzantium, a dispute arose between Bishop Cyril and Bishop Nestorius. The latter lost and was expelled from Constantinople. So he sought refuge in the Middle East in areas found in present day Iraq and in Egypt. Nestorius carried all his classical cultural baggage with him including that of being a doctor, originating a medical concept very similar to that found in Ancient Rome. Great importance was given to hygiene: very advanced hospitals were built in Baghdad, other Iraqi cities, and in Cairo along the lines of those constructed by the Romans. In this Arab era no importance was assigned to anatomy, but the concept of holistic medicine continued. So the notion of washing oneself frequently (10) remained firmly established. In Arab medicine, religion also was very influential. One of the Koran's concepts was that the human body should not be cut because, along with the blood, the soul also would leave the body. This meant that surgery could not be practised. Moreover, this belief, disallowed dissection for 24 hours after death for fear of damaging the soul. In order to prevent this happening, the Arabs invented cauterization (which is still used today in order to block the vessels temporarily during a surgical operation) (11). At that time eschar had to be followed by suppuration in order to create pus, bonum et laudabile, fully respecting the therapy of the time, even it often led to the patient's death. Furthermore, to their credit, the Arabs handed down the writings of the Ancient Greeks, that had reached them through the Nestorians or as gifts from various Western princes, by scrupulously translating them into Arabic whilst leaving the parallel Greek test. Great Physicians were Rhazes (864-925) and Avicenna (980-1037) . Around the half of 1200 the Syrian Ibn-Al-Nafis (1213-1288) described the pulmonary circulation. It is unlikely, however, that his discovery did influence western medicine since it surfaced only in 1924.

Although in the east the Arab developed an extremely advanced society based on the ancient inheritance of the classic, and sustained by the nascent Islamic conception that translated and commented on the ancient texts, in the West it was a period of obscurantism and return to theurgic medicine. The saints were believed to be adjuvant and their relics were thought to have miraculous powers. Wars were even fought over these relics (13). The concept of the Cult of Saints was particularly widespread in this period. The most famous among the adjuvant saints were Saints Cosmas and Damian (14): they were the patrons of the Medici family as well as of doctors, and were called anargiri because they did not ask for fee. A posthumous "miracle" was attributed to them: they attached a leg taken from a black man's cadaver to the sacristan of their church, who had a gangrenous leg. There were protecting saints for every organ and against all diseases: St. Lucy was protector of the eyes, St. Apollonia of the teeth, St. Blaise for the throat, St. Fiacre protected against haemorrhoids, St. Anthony against leprosy, and St. Roch against plague, St. Anne parturition and St. Agatha against diseases of breast.

The first universities were founded in this period. At first, there were the Studia, which were institutes sponsored by the lay civil community, whereas the university ("Universitas studiorum"), was, at first, a spontaneous phenomenon, originated where itinerant students chose a valid teacher by offering him a salary. In this case power lay in the hands of students who could change teacher when they wished if they were not satisfied. The emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, was the first to finance these students, giving them financial support if they remained and settled in his city. Then, the Church entered into the situation and the University could only become such through the issuing of a Papal Bull. The first university in the western world given a Papal Bull was the University of Bologna. The first Universities were based on the liberal sciences of the trivium (rhetoric, dialectics and grammar) and of the quadrivium (mathematics, geometry, astronomy (15) and music (16)). Medicine only entered into university disciplines about 150 years later: in Bologna the physician Taddeo degli Alderotti (1223-1303) argued medicine's cases with the rhetors, managing to elevate the status of medicine into a position alongside the other university disciplines. --------------------------------------------------

(1) One recalls Herophilus's torcular. |

|

|

From the notes of Lorenzo Fiorin |

As already mentioned, the most important school in Alexandria was the methodical school. This did not no rest on the philosophy of the four elements, but to the rival philosophy, the atomistic theory of Democritos (who lived between the V and the IV centuries B.C.). The Hippocratic conception was finalistic, analogous to that of Aristotle, whereas the theory of Democritos was based on the case. According to this school the pores had great importance: so, according to whether the pores were open or closed, the patient had a condition of looseness or tension respectively. It was necessary to do everything to keep the pores in their normal open mode, and attention had to be paid to how one washed, to the water's temperature This concept, reported by Galen, became the cause of extremely poor hygiene in Medieval times because it was interpreted wrongly and taken to mean that water was condemned for causing the pores to close.

As already mentioned, the most important school in Alexandria was the methodical school. This did not no rest on the philosophy of the four elements, but to the rival philosophy, the atomistic theory of Democritos (who lived between the V and the IV centuries B.C.). The Hippocratic conception was finalistic, analogous to that of Aristotle, whereas the theory of Democritos was based on the case. According to this school the pores had great importance: so, according to whether the pores were open or closed, the patient had a condition of looseness or tension respectively. It was necessary to do everything to keep the pores in their normal open mode, and attention had to be paid to how one washed, to the water's temperature This concept, reported by Galen, became the cause of extremely poor hygiene in Medieval times because it was interpreted wrongly and taken to mean that water was condemned for causing the pores to close.  However, the most characteristic element of Roman sanitation was hygiene. The Romans washed a great deal, to which the use and the number of thermal baths existing at that time bears witness. Leaving an extremely important mark on western culture, the most important doctor in Roman times was the Pergamese Galen (129 A.D.-200 A.D.) (6). He was the son of the kings' architect who thus came from a wealthy family and after his apprenticeship at Alexandria went to Rome where he was doctor to the gladiators, acquiring anatomical experience, even though he followed Greek concepts, and he dissected animals above all else. The most studied animal was the pig ("the animal most similar to man" said Galen) and the monkey (7). Galen's instinct lead him to realise the fundamental importance of the organs and their effective role. For example, he understood that the urinary bladder did not produce urine but that this came from the ureter (he demostrated this by joining the ureters together) and for the first time described the recurrent nerve and its role in fonation. He was very important as a practicing physician: basing his treatment on medicinal plants, he introduced several pharmaceutical drugs. For example, use of willow bark, laudanum (an opium tincture) as anaesthetics.

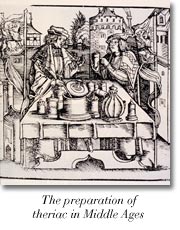

However, the most characteristic element of Roman sanitation was hygiene. The Romans washed a great deal, to which the use and the number of thermal baths existing at that time bears witness. Leaving an extremely important mark on western culture, the most important doctor in Roman times was the Pergamese Galen (129 A.D.-200 A.D.) (6). He was the son of the kings' architect who thus came from a wealthy family and after his apprenticeship at Alexandria went to Rome where he was doctor to the gladiators, acquiring anatomical experience, even though he followed Greek concepts, and he dissected animals above all else. The most studied animal was the pig ("the animal most similar to man" said Galen) and the monkey (7). Galen's instinct lead him to realise the fundamental importance of the organs and their effective role. For example, he understood that the urinary bladder did not produce urine but that this came from the ureter (he demostrated this by joining the ureters together) and for the first time described the recurrent nerve and its role in fonation. He was very important as a practicing physician: basing his treatment on medicinal plants, he introduced several pharmaceutical drugs. For example, use of willow bark, laudanum (an opium tincture) as anaesthetics.  However, together with these useful drugs, he used some completely useless potions, amongst which were theriac (8), a broth containing the strangest of things: goat dung, pieces of mummy, adder's heads. The only good thing about this brew was the fact that it was boiled for long time sterilising the material contained in it. It was used until the end of the 18th century, generally being produced once a year under the responsibility of the magistrate in the various cities, and then sold in the pharmacies. Notwithstanding his numerous intuitions, possibly because the most accepted theory of the time was the Hippocratic, Galen embraced the theory of the humours. Furthermore, he emphasised the therapeutic aspect of the materia peccans. Among the materia peccans was pus, which was called "bonum et laudabile" by Galen because it was an expression of materia peccans that had to be eliminated: he understood that pus is a substance that does require elimination. However, unfortunately and above all by Galen's followers, this theory was exploited very narrowly: in fact, Galen's writings were used to advocate the formation of pus in order to promote healing of wounds. This concept continued to be considered valid until the end of the 16th century.

However, together with these useful drugs, he used some completely useless potions, amongst which were theriac (8), a broth containing the strangest of things: goat dung, pieces of mummy, adder's heads. The only good thing about this brew was the fact that it was boiled for long time sterilising the material contained in it. It was used until the end of the 18th century, generally being produced once a year under the responsibility of the magistrate in the various cities, and then sold in the pharmacies. Notwithstanding his numerous intuitions, possibly because the most accepted theory of the time was the Hippocratic, Galen embraced the theory of the humours. Furthermore, he emphasised the therapeutic aspect of the materia peccans. Among the materia peccans was pus, which was called "bonum et laudabile" by Galen because it was an expression of materia peccans that had to be eliminated: he understood that pus is a substance that does require elimination. However, unfortunately and above all by Galen's followers, this theory was exploited very narrowly: in fact, Galen's writings were used to advocate the formation of pus in order to promote healing of wounds. This concept continued to be considered valid until the end of the 16th century.  The Arab civilisation reached its zenith in Islamic Spain. At Cordoba in particular there were great physicians as Maimonides, Giuannizzius, Rhazes, Albucasis, and Averroes (1126-1198) . The period of the Moorish civilisation (12) in Europe was the apex of Arab civilisation. After the fall of the Moors the Arab empire collapsed and their knowledge came back to Europe, particularly to Montpellier and Salerno.

The Arab civilisation reached its zenith in Islamic Spain. At Cordoba in particular there were great physicians as Maimonides, Giuannizzius, Rhazes, Albucasis, and Averroes (1126-1198) . The period of the Moorish civilisation (12) in Europe was the apex of Arab civilisation. After the fall of the Moors the Arab empire collapsed and their knowledge came back to Europe, particularly to Montpellier and Salerno.  As already mentioned, after the fall of the Arab kingdoms the Spanish Muslim scientists settled above all in France, at Montpelier, and in Italy in Salerno, where the so-called Salerno school flourished and which, according to legend, was founded by a Greek, by a Latin and by a Hebrew and by an Arab a little before the year 1000. A plethora of Greek and Arab manuscripts were to be found in this school. As a result, there was a return to Greek and classical culture and Hippocratic medicine. In this epoch great importance was placed on moderation in diet and in wine. In addition, advice was given on what needed doing and what, on the other hand, should be avoided. For example, overdoing amorous activities was to be avoided, reading by candlelight should also be avoided, as should forcing oneself during defecation, and not overindulging in wine was essential. The principles of hygiene returned, of washing one's hands frequently, of wholesome healthy fresh air. Great importance was given to the concept of temperament, four of which were identified: the jovial temperament, the loving or amorous temperament, the choleric and the phlegmatic.

As already mentioned, after the fall of the Arab kingdoms the Spanish Muslim scientists settled above all in France, at Montpelier, and in Italy in Salerno, where the so-called Salerno school flourished and which, according to legend, was founded by a Greek, by a Latin and by a Hebrew and by an Arab a little before the year 1000. A plethora of Greek and Arab manuscripts were to be found in this school. As a result, there was a return to Greek and classical culture and Hippocratic medicine. In this epoch great importance was placed on moderation in diet and in wine. In addition, advice was given on what needed doing and what, on the other hand, should be avoided. For example, overdoing amorous activities was to be avoided, reading by candlelight should also be avoided, as should forcing oneself during defecation, and not overindulging in wine was essential. The principles of hygiene returned, of washing one's hands frequently, of wholesome healthy fresh air. Great importance was given to the concept of temperament, four of which were identified: the jovial temperament, the loving or amorous temperament, the choleric and the phlegmatic.  So, above all, great importance was given to what one ate in relation to the temperament. For example, if a person was very choleric, it meant he had a great deal of bile and too much fire. It was necessary to tone down and dampen such a temperament by making the person eat fish from marshes, which is cold, or otherwise the coot (which was considered to be a fish). Emphasis was place on examining the ill and on examining the urine. There was a degree of development in surgery, but not in the condition of the surgeon, who was still considered to be a sort of servant (as underlined by his raiment) and not a doctor.

So, above all, great importance was given to what one ate in relation to the temperament. For example, if a person was very choleric, it meant he had a great deal of bile and too much fire. It was necessary to tone down and dampen such a temperament by making the person eat fish from marshes, which is cold, or otherwise the coot (which was considered to be a fish). Emphasis was place on examining the ill and on examining the urine. There was a degree of development in surgery, but not in the condition of the surgeon, who was still considered to be a sort of servant (as underlined by his raiment) and not a doctor.